Speciale

Which African language do you speak?

How much can change in 5 days? As I discovered, quite a lot. When I first arrived to Kampala I found a group of more or less shy art students with more or less certain ideas of who they were. When I left Kampala 5 days later, I got to know 20 individuals, with their certainties shattered, but their confidence solidified. It wasn’t some kind of magic. They were simply put at work by Simon Njami during the 5-day intensive AtWork workshop, held in partnership with Makerere University’s art school and art gallery and Maisha Foundation.

5 days of questioning, sharing, exchanging, elaborating, metaphorically and literally taking their shoes off and exploring the notions, spaces and territories, where they have not set their foot before. 5 days of the “collective phsychodrama”, during which the individuals emerged. The individuals that started asking themselves questions and trying to find the answers, opening up their minds and creative channels. The individuals who started to realize that to be an artist you also have to be a thinker and, above all, a human being. The individuals who started to understand that to know anything you have to first question everything you think you know. This process of self-reflection has found its creative expression on the pages of Moleskine notebooks, which were created during the workshop and which will be exhibited at the Makerere Art Gallery from March 19th to April 11th.

The workshop is over, but the process has just started. It will be up to the students to continue to be stimulated by what they have found out about each other and about themselves. It will be up to us to keep discovering the worlds and personal stories that each AtWork notebook contains. And to be inspired by them. Let’s start with that of Gloria Kiconco, a young writer and Kampala AtWork participant, who decided to share with us her reflections on the question “Why Africa?”.

Elena Korzhenevich,

lettera27

Gloria Kiconco during AtWork Kampala workshop. Photo by Solomon E. Okurut. Courtesy of the author

My story with Africa started with rejection. I still ask myself why her? She is not really my mother, sister, or friend. We have very little in common and only blood has tethered me to this woman who, I often imagine, disregards my being.

My mother tells me I was an easy birth and a quiet baby. I think, even then I did not want to be a bother and from then my story was a search for belonging. But you already know my story because it is that of so many Africans who migrated and lost themselves along the way. The difference is details.

I was in the United States. I took off my language, my extended family, my ‘heritage’ and dressed in individualism so as to be accepted. It was a labour twelve years in the making and just as I grew into this new me, I was called back ‘home’ to Uganda. What kind of home is it where you don’t recognize the greeting?

So, when I came back to Africa, she did not recognize me. She also remains a stranger to me.

There is no rejection more painful than rejection of self. Cultural displacement is an undiagnosed autoimmune disease that turns the body against itself. Why was I the blood cell Africa did not recognize? The patch of skin she dismissed as a scar and never celebrated as a birthmark?

Most Ugandans I meet ask me which language I speak and I tell them English. Then they ask me which African language I speak and I tell them, Ugandan English. Most Ugandans I meet call me white. Sometimes I think they are right because I often have more in common with white boys from Colorado than I do with black women from Kampala.

But then I remember the names they called me in the US. Is it better to be called white with joking disdain than ‘white-washed’ with obvious disgust?

Africa rejected me the least and everyone said we would get along well, that I wouldn’t feel so unwanted. In truth she was the only one who would claim me. I imagine she did so begrudgingly, sending me to the kitchen when visitors came around. She liked to bring me out when white people visited so I could translate cultural differences, but would rather I go to pick firewood when family visited. Not to the garden. She did not trust me with her crops, her food, and her children.

She did not make clothes for me because kitenge made me look like a caricature and she hates to be laughed at.

I could not look her in the eye. I was the child who did something wrong and did not remember committing the crime. I just wanted her to laugh as warmly with me as she did with others, perhaps to let me in on the joke (I hoped I was not the joke).

It is amazing what you can compromise for the sake of acceptance.

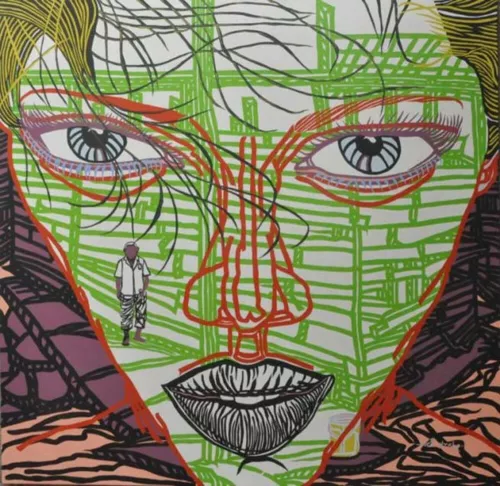

Boris Nzebo, Untitled, in Down Town (serie), 2014. Courtesy of the artist

This was the exact theme I was exploring during the AtWork workshop in Kampala. While others explored their identities as ‘artists’, ‘writers’, and ‘curators’, I was caught in flashbacks of this relationship I have with Africa and what I gave up for her to accept me.

I discovered this: I was confining Africa to one spectrum, framed by the abrasive memories of not being ‘African’ enough. I cannot even begin to address this issue of authenticity because the complexities of my (and many others’s) identity completely rejected definition. ‘Third culture kid’, ‘African in Diaspora’, and my attempted brand of ‘original African American’ all did not fit.

So I stopped looking at these issues of identity: who I am, who is and is not African, and what we all have to do with each other. As soon as I stopped this restrictive search for myself, I was able to look Africa in the eye.

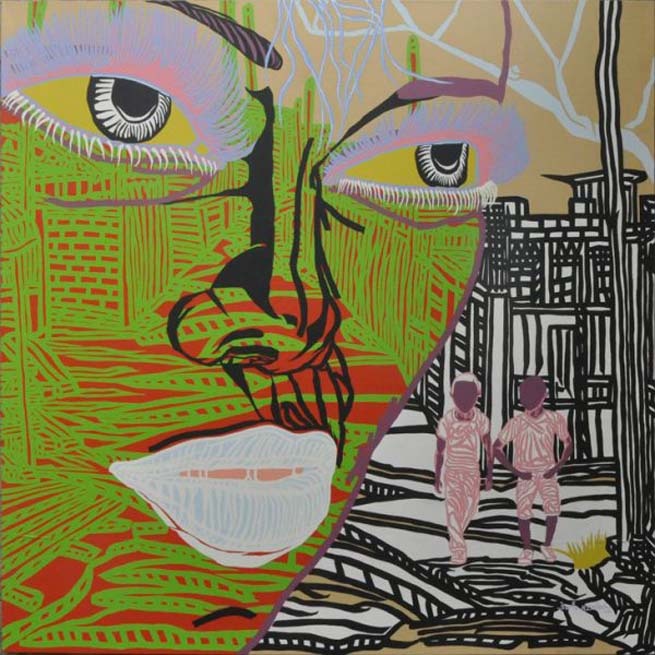

Boris Nzebo, Untitled, in Down Town (serie), 2013. Courtesy of the artist

Why Africa? Because she and I share the language of art.

Her art opens up compartments of me I thought were long ago archived and even possibly incinerated. I have seen reflected in poems, films, paintings, installations, sculptures, and scripts the stories I could not write to myself. The words I could not write to myself in private journals are sung on stages.

I found out how, despite being the only ‘me’, there was absolutely nothing special about me. My story was a verse in an epic poem that told one history, an echo of the stories that started before mine, a reverberation of poems recited across oceans and valleys.

How else could Melissa Kiguwa pen the poems I could not express or Lillian Nabulime sculpt my suspicions into reality or Eria Nsubuga collage my concerns on socio-political issues unaddressed? Why is it when Ronex Ahimbisibwe (or his art) speaks, my conscience nods its head? And these are just a handful from Uganda. You see, Africa has a source of creation whose boundaries we have never seen and may never see.

I have an incredible urge now to bring these narratives to other Ugandans in hopes that they may find themselves reflected within. But also because threading these stories with context and history and artistic intention, will lend more strength and meaning to the work, even to people who disregard art as a pastime (at best).

I believe the source of meaning and relevance in anything is in the context, the people, and the ideas. These may be communicated on theoretical levels among the educated but they are also communicated by the gut reaction to an artwork. I want to tell the story this art is telling, the story and ideas of the people behind it in order to give it meaning and relevance.

The secrets I share with Africa I whisper through storytelling and poetry and she whispers back in unabashed colour and arresting composition. My way is not for everyone. Other people may whisper secrets shared in languages of technology, spirituality, or business.

Africa and I have finally found we have something in common. We share amazing stories in this language of ours and I would find ways to translate them for you.

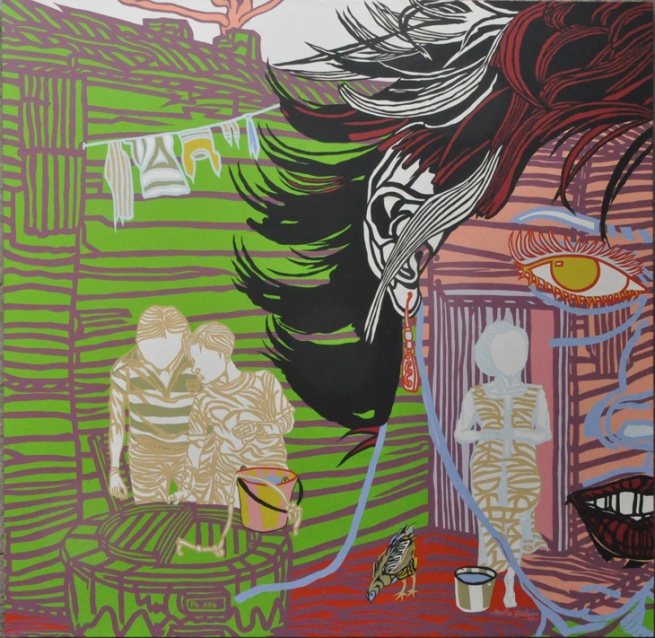

A special thank you to the artist Boris Nzebo for having granted us the permission to use his images to illustrate the article, taken from the series Down Town (2013).

Why Africa? For many years lettera27 has been dedicated to exploring various issues and debates around the African continent and with this new editorial column we would like to open a dialogue with cultural protagonists who deal with Africa. This will be the place to express opinions, tell their stories, stimulate the critical debate and suggest ideas to subvert multiple stereotypes surrounding this immense continent.

With this new column we would like to open new perspectives: geographical, cultural, sociological. We would like the column to be a stimulus to learn, re-think, be inspired and share knowledge. For the opening piece we asked our partners, intellectuals and like-minded cultural protagonists from all over the world to answer one key question, which also happens to be the name of the column: "Why Africa?". We left the question deliberately open, inviting each of the contributors to give us their perspective on this topic from their own context. This first piece is a collection of some of the answers we received, which aims to open the conversation, pose more questions and hopefully find new answers.

Elena Korzhenevich,

lettera27