Speciale

Out of sight, out of mind

Why Africa? For many years lettera27 has been dedicated to exploring various issues and debates around the African continent and with this new editorial column we would like to open a dialogue with cultural protagonists who deal with Africa. This will be the place to express opinions, tell their stories, stimulate the critical debate and suggest ideas to subvert multiple stereotypes surrounding this immense continent.

With this new column we would like to open new perspectives: geographical, cultural, sociological. We would like the column to be a stimulus to learn, re-think, be inspired and share knowledge. For the opening piece we asked our partners, intellectuals and like-minded cultural protagonists from all over the world to answer one key question, which also happens to be the name of the column: "Why Africa?". We left the question deliberately open, inviting each of the contributors to give us their perspective on this topic from their own context. This first piece is a collection of some of the answers we received, which aims to open the conversation, pose more questions and hopefully find new answers.

Elena Korzhenevich,

lettera27

Here the column's introduction: Why Africa?

Back in 2004, during a period where my work largely dealt with architecture, I visited Asmara. Though that trip originally had nothing to do with the built urban environment, it became a turning point of sorts. For one, I was mesmerised by the city’s brick and mortar heritage - some 400+ modernist buildings from the 1930s and 1940s in various states of repair and disrepair. The biggest impact however, was that it left me with many questions; I found myself mentally circling around notions of memory, amnesia and heritage. In an effort to learn about that city’s history, I began a quest for sources on its Italian colonial past and architectural endowment. Asmara is home to one of the largest collections of buildings reflecting numerous Modernist movements, including Novecento, Art Deco, Rationalism, Futurism and Monumentalist architecture.

Given that significance, it seemed natural that such a remarkable city would be, or should be recorded in various bodies of knowledge. Ostensibly, it would be mentioned in dissertations, documented in glossy art books, and be part of innumerable intellectual discussions on architecture, or Fascist propaganda and nation-building. For instance like this illumination by Professor Naigzy Gebremedhin, a leading intellectual on the subject: “Modernist architecture stands on the shoulders of three giants of architecture. Two are of German origin, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius, the third is French, Le Corbusier. In some ways it is intriguing that Asmara provides an opportunity to reflect on how their ideas worked out in a place far away from Germany, France or Italy, the countries where they developed their new ideas, and also far from the twin ideological and political nightmares of Nazism and Fascism in which modernist architecture developed in the Europe of the 1930s.” [1]

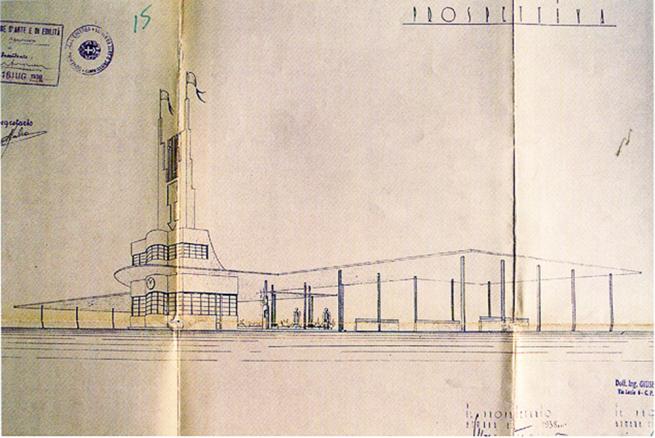

Architectural sketch of the Fiat Tagliero gas station documented in the book Asmara: Africa's secret modernist city.

Architectural sketch of the Fiat Tagliero gas station documented in the book Asmara: Africa's secret modernist city.

The reality nonetheless was quite different. As of the early 2000s, there were only two keys sources. Gebremedhin had spearheaded both; the first was CARP, a government initiative[2] established in 1997 to assess and preserve the city’s architectural heritage, and the second, an in-depth scholarly book [3] published in 2003. Both stood out as seminal locally led projects, in what otherwise could be described as a vacuum. In fact CARP would be instrumental during those early years [and until 2007] to lay the groundwork for policy development on cultural management in Eritrea. A positive sign, to see that culture was being recognised as important to national identity, education and so forth. For it is as curator Hans Ulrich Obrist reminds us, that “public bodies have a duty toward the support of culture, that which has become our heritage” [4]. However, as critical as those early efforts were in 2004, both were essentially only accessible in Eritrea’s capital city, and mostly relegated to analogue spheres.

Looking back, there were different reasons for the omission of Asmara’s modernist legacy from contemporary discourse at large, reasons that could also explain why despite its size, it was being described as Africa’s secret modernist city. The thirty year war of independence from neighbouring state Ethiopia ending in 1991, and subsequent conflict that began in the late 1990s were the most obvious and easiest to point out.

Yet the overarching invisible state of Asmara’s architecture, and its relegation to very limited circles of intellectual circulation left me troubled. Call it a quandary on the past, the present and the future. Art historian Erwin Panofsky states “the future is often invented by fragments of the past.” [5] No wonder alarm bells were suddenly ringing; the road lying ahead was coming into view. For it is disquieting to consider what happens when the past is significantly and materially limited, skewed, or altogether invisible. Certainly one obvious future is that bodies of knowledge that could endow intellectual diversity would be curtailed, and hampered. And so what originally seemed like a simple question of sourcing information, actually revealed something much deeper. That the omission of knowledge is equally as powerful if not more powerful than the presence of knowledge. For in that invisibility, is the clear visibility of power and who holds it.

Missla Libsekal is an independent publisher and writer based in Vancouver. She is the founder and editor of online platform anotherafrica.net, a journal dedicated to contemporary art and design. "The arts are not a first-world luxury, Another Africa is intended to be a constant reminder of this.”

[1] Gebremedhin, N. (2007, December 6). Asmara, Africa's Secret Modernist City. African Perspectives: Dialogue on Urbanism and Architecture. Lecture conducted from Delft University of Technology, Delft.

[2] Cultural Assets Rehabilitation Project of Eritrea.

[3] Denison, E., Ren, G., & Gebremedhin, N. (2003). Asmara: Africa's secret modernist city. London: Merrell.

[4] Obrist, H. (2014). The Future of Art and Patronage. In A. Lamm (Ed.), Sharp tongues, loose lips, open eyes, ears to the ground (p. 63). Berlin: Sternberg Press.

[5] Obrist, H. (2014). After the Moderns the Immaterials. In A. Lamm (Ed.), Sharp tongues, loose lips, open eyes, ears to the ground (p. 41 - 42). Berlin: Sternberg Press.

With the support of